Communication Theory: WYSIWYG

Communication Theory in the Field of Design

Design is often perceived as a visual or aesthetic activity, focused on form, style, and novelty. However, within contemporary culture, design functions primarily as a communicative practice. It produces meanings, frames interpretations, and shapes relationships between creators, audiences, and social contexts.

Communication theory allows us to move beyond an intuitive understanding of design and approach it as a structured process of meaning-making embedded in culture.

From a sociocultural perspective, communication is not a linear transmission of messages but a dynamic process in which meaning is constructed through interaction, shared symbols, and social norms. In this sense, design does not simply «deliver» a message; it participates in cultural dialogue. Visual language, typography, interfaces, and narratives operate as symbolic systems that audiences interpret differently depending on their experiences, values, and media environments.

One of the key challenges of contemporary design lies in the diversity and fragmentation of audiences. Digital media ecosystems encourage multi-screening, rapid content consumption and selective attention. Audiences are no longer passive recipients; they actively choose, reinterpret, and sometimes resist messages. The Uses and Gratifications approach helps explain this shift by framing audiences as goal-oriented participants who engage with media to satisfy specific needs, such as identity construction, social connection or entertainment. For designers, this means that communication strategies must account for audience motivations rather than rely on universal visual solutions.

Another important concept for understanding design as a sociocultural practice is dialogic communication. In contrast to one-way persuasive messaging, dialogic approaches emphasize interaction, feedback, and relationship-building. Brands and cultural projects that fail to acknowledge this dialogic dimension risk creating communication that is technically polished but socially ineffective. Design decisions — from visual hierarchy to tone of voice — can either open or close space for dialogue, influencing whether audiences feel invited into a relationship or positioned as mere spectators.

Semiotics further reinforces this perspective by framing design as a system of signs. Colors, materials, layouts, and visual metaphors carry culturally specific meanings that are not fixed but negotiated. A design choice that signals trust, innovation, or exclusivity in one context may produce entirely different interpretations in another. Communication theory provides tools to anticipate these interpretive gaps and design with cultural sensitivity rather than aesthetic assumption.

Finally, adopting a sociocultural view highlights the ethical dimension of design. Communication is never neutral: it reinforces certain values, norms, and power relations while marginalizing others.

By understanding design as a communicative act situated within culture, designers take responsibility not only for how things look, but for how they shape social interactions and collective meanings.

In this project, we approach design as a sociocultural communication system rather than a visual artifact. Communication theory serves as a methodological foundation that informs how meanings are constructed, how audiences are addressed, and how dialogue is facilitated. This perspective directly shapes the imaginary brand developed in the following sections and explains the need for differentiated communication strategies for general and professional audiences.

Presentation for a General Audience

WYSIWYG is a hackathon format built on radical transparency. No hidden requirements. No unexpected technologies. No last-minute surprises.

What you see is exactly what you get.

Hackathons are often presented as opportunities for growth, networking, and experimentation. In reality, many of them function as black boxes. Participants arrive without fully understanding: 1. the task format, 2. the required technologies, 3. the evaluation criteria.

Stories like these are common: you come motivated, ready to work — and only then discover that the task requires tools or languages you’ve never used.

Leaving early feels less like a choice and more like a failure.

For young developers, hackathons are not just competitions. They are social environments where self-confidence, reputation, and public image are at stake.

Unclear communication turns every participation into a risk.

WYSIWYG was created to eliminate this uncertainty.

We believe that transparency is not an extra feature — it is a form of respect. Before joining a hackathon, participants know what they will be working on, which tools are required, how their work will be evaluated.

Each WYSIWYG hackathon clearly communicates technology stack, difficulty level, task structure, judging logic.

Transparency gives participants agency.

You can prepare in advance, choose challenges that match your skills, decide consciously whether to participate.

No hidden complexity. No misleading promises.

When expectations match reality, anxiety decreases, confidence increases, participation becomes inclusive rather than competitive by default.

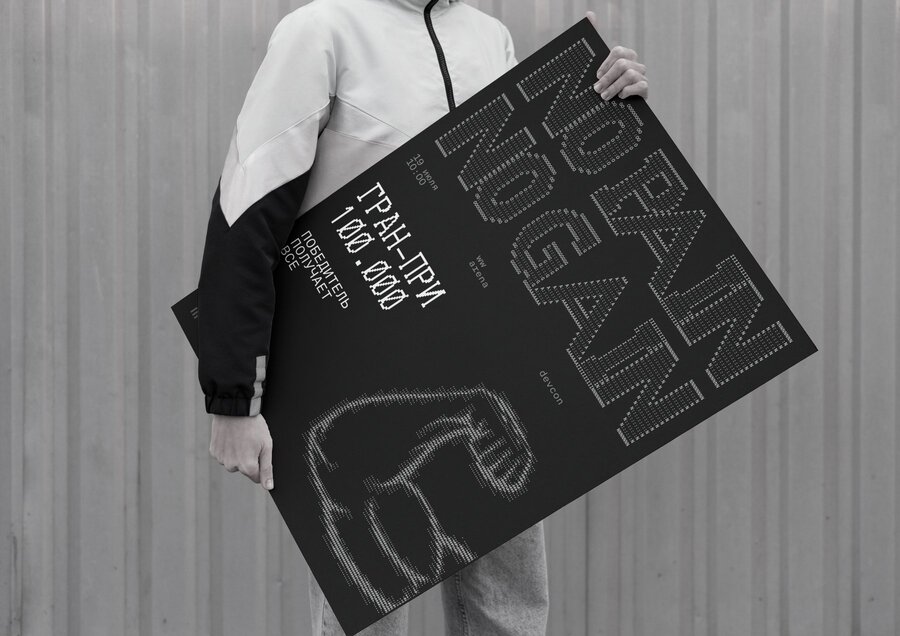

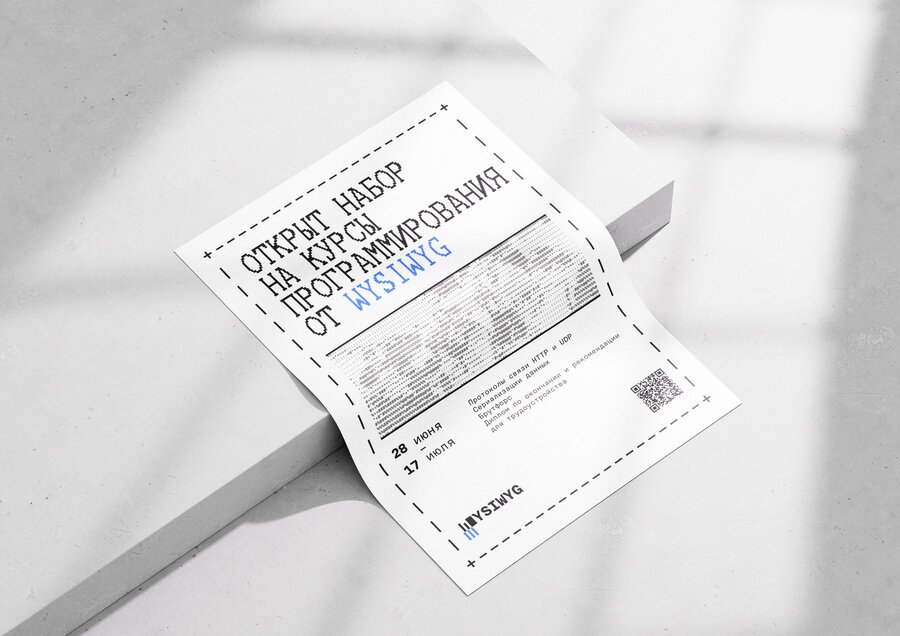

WYSIWYG uses glitch aesthetics and ASCII graphics to visually expose what is usually hidden.

Errors, systems, and processes are not masked — they are made visible.

WYSIWYG offers a hackathon experience without surprises.

Just clarity. Just honesty. Just the work.

Presentation for a Professional Audience

Professional audience: designers, educators, jury, communication specialists.

WYSIWYG is a communication-driven hackathon brand designed as a response to structural opacity in contemporary competitive programming events.

Communication challenge

Most hackathons rely on asymmetrical information distribution. Organizers retain control over task complexity, tools, and evaluation criteria, while participants are expected to adapt in real time. This creates a power imbalance and uncertainty.

For young developers, participation is tied to peer recognition, self-efficacy, professional identity formation. Communication failures therefore have social consequences. From a Uses and Gratifications perspective, participants are not passive recipients of challenges.

They engage with hackathons to: test competence, gain recognition, build social capital.

Opacity undermines these motivations.

WYSIWYG reframes the hackathon from a «test under uncertainty» to a transparent communicative system.

Strategic Positioning

WYSIWYG positions itself as a transparent, communicative system rather than a «test under uncertainty».

Strategic pillars:

- Transparency as core value

- Participant empowerment

- Ethical and procedural clarity

This positions the brand beyond competitive programming as a model for ethical event design.

Transparency functions as an ethical and strategic foundation, not as an informational add-on.

Every communicative element aims to reduce uncertainty before participation begins. Rather than one-way promotion, WYSIWYG adopts a dialogic approach: clear expectations, explicit conditions, anticipatory feedback. Participants are positioned as informed decision-makers.

Target audience & motivations

Primary audience: young, professional developers seeking: • peer recognition, • professional identity validation, • competence testing, • social capital building.

Secondary audience: educators, industry mentors, and jurors who value process transparency.

Insight: opacity undermines intrinsic motivations; transparency aligns participation with professional values.

Brand Voice & TOV

Brand voice is precise, clear, procedural, but friendly and relatable. It avoids hype or motivational exaggeration, though warmly persuades and focuses on informing and enabling decision-making.

The chosen tone of voice reflects ethical positioning and supports a transparent user experience.

Visual & Semiotic Approach

The visual system employs glitch aesthetics and ASCII art as semiotic tools. They reference system exposure, technical infrastructure, the rejection of polished ambiguity.

Visual language reinforces the message of openness.

Dialogic Communication

WYSIWYG emphasizes two-way interaction over promotional one-way messaging

Each channel functions as a distinct communicative space: the website provides full disclosure, social media explains processes rather than outcomes, offline formats replicate the same logic of transparency.

By aligning encoding (organizers’ intentions) and decoding (participants’ interpretations), WYSIWYG minimizes communicative noise.

Expectation management becomes a design task.

Managing Expectations & Ethical Dimension

Expectation alignment of coding (organizer intent) + decoding (participant interpretation) minimizes communicative noise. Transparency redistributes control, lowers barriers to entry, reduces exclusion. WYSIWYG’s design is a social intervention as well as a functional framework.

Communication Theory as Basis for the Presentations

The development of the WYSIWYG project was directly shaped by the concepts and frameworks introduced in the Communication Theory course. Rather than serving as a theoretical reference added after the design process, communication theory functioned as a methodological foundation that informed key decisions at every stage of the project.

First, the course reframed our understanding of communication as a process of meaning-making rather than message transmission. This perspective allowed us to identify the core problem of contemporary hackathons not as a lack of opportunities, but as a communicative failure rooted in information asymmetry. By applying this framework, we approached hackathons as communicative systems in which expectations, interpretations, and social contexts play a critical role.

The Uses and Gratifications approach was particularly influential in shaping the audience strategy. Instead of treating participants as a homogeneous group, we analyzed their motivations — such as skill validation, social recognition, and identity formation. This shift formed both the general and professional presentations, where transparency is framed not as a feature, but as a response to concrete audience needs. The structure of the participant-facing presentation reflects this logic by prioritizing clarity, agency, and informed choice.

Dialogic communication theory further guided the positioning of the brand. Traditional hackathon promotion often relies on one-way persuasive messaging, emphasizing excitement while withholding procedural details. In contrast, WYSIWYG adopts a dialogic model in which communication anticipates questions, reduces uncertainty, and respects participants as active agents. This approach influenced not only the tone of voice but also the selection of channels and touchpoints, all of which are designed to support long-term trust rather than short-term engagement.

Semiotic theory played a key role in the development of the visual language. Glitch aesthetics and ASCII art were not used as stylistic references to «tech culture», but as communicative signs that expose underlying systems and processes. These visual elements reinforce the brand’s commitment to transparency by making technical structures visible rather than concealing them behind polished surfaces.

Finally, the sociocultural perspective emphasized the ethical dimension of communication design. Lectures addressing power relations, ideology, and participation highlighted how opaque communication formats can reinforce exclusion and social anxiety. This understanding positioned WYSIWYG not merely as a brand, but as a critical intervention into the culture of competitive programming events.

Overall, communication theory provided the conceptual tools to move from intuition to intentionality. It enabled us to design a brand that operates as a coherent communicative system, aligns meaning across different audiences, and demonstrates how theoretical frameworks can be applied to contemporary design practice in a concrete and socially relevant way.

Курс: Communication Theory: Bridging Academia and Practice — Вышка Digital | Smart LMS [Электронный ресурс]. Режим доступа: https://edu.hse.ru/course/view.php?id=133853 (дата обращения 12.12.2025)

Carey, J. W. (2009). Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society. New York: Routledge.

Craig, R. T. (1999). Communication theory as a field. Communication Theory, 9(2), 119–161.

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In The Uses of Mass Communications. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Kent, M. L., & Taylor, M. (2002). Toward a dialogic theory of public relations. Public Relations Review, 28(1), 21–37.

Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/decoding. In Culture, Media, Language. London: Hutchinson.

Chandler, D. (2017). Semiotics: The Basics. London: Routledge.

Couldry, N. (2012). Media, Society, World: Social Theory and Digital Media Practice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. New York: Springer.