Portable architecture

The first thing we study in different cultures is architecture — monumental buildings, temples, mausoleums, sacrificial and spiritual sites. They took many decades, sometimes centuries, to build — but they weren’t really part of the everyday lives of the people who built them.

Where did ordinary people who couldn’t afford palaces and castles live? How have barabaras and bahay kubos changed after years of colonization and globalization? Do people still live there today?

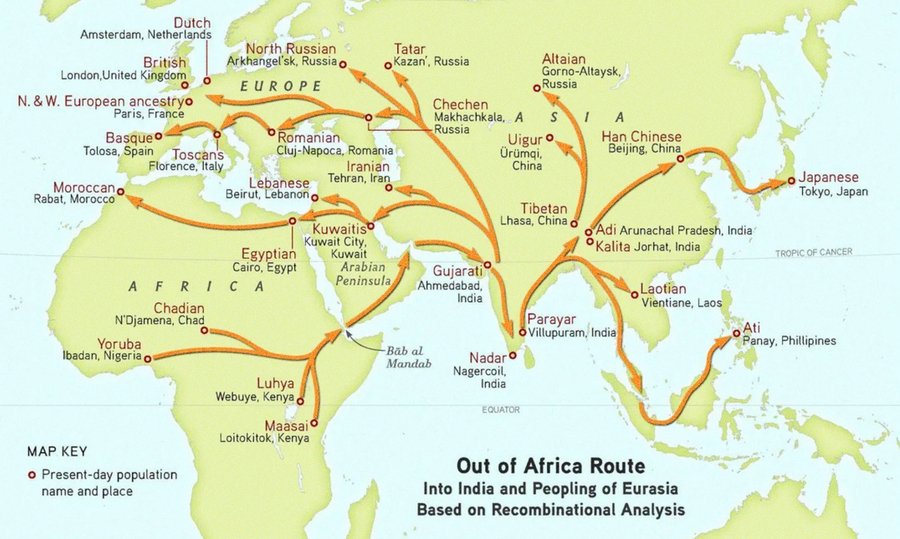

We organized this study geographically, following the general trend of early human migrations.

Map of early human migrations, National Geographic

Mammoth House // Geodesic igloo dome

Africa

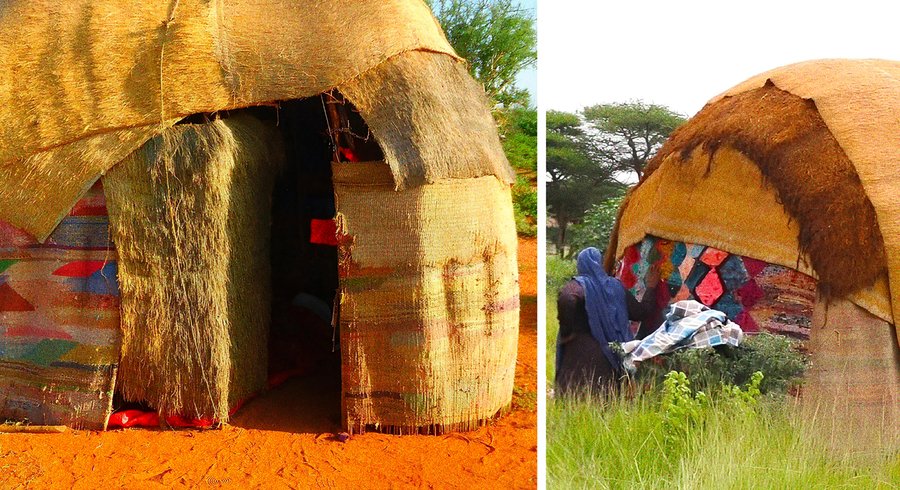

Aqal or buul is an example of a circular hut that has changed little over the centuries.

It is a traditional house and cultural heritage of the Somalis, woven from many colored ropes, poles, natural fibers, tree bark, contains almost no furniture inside, had protection from sun, wind and rain, can be reassembled and moved in a single day.

Ifrah Mansour, a Somali performance artist and refugee currently living in Minnesota, describes both the process of weaving and entering an aqal as healing.

«When people go inside the hut, some have said that they feel cocooned. Some feel cool and have an instant need to sit down and adjust their posture» © Curators of College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University, 2024

Agal hut, Source unknown // Somali Museum of Ottawa // Somali Museum of Melbourne

Somali Museum photo archive

However, the modern, career-oriented, male-dominated society is challenging this tradition, which has proven sustainable for the region and its ecology over the centuries.

British colonists brought their brick and mortar construction standards, which do not allow for proper drainage during the rainy season, leading to droughts. The expensive, difficult and time-consuming construction process also can’t meet the needs of Africa’s rapidly growing population and economy.

Traditionally, the construction of an aqal was done by a group of friendly women and family members, and the place was meant to be sturdy, clean, warm, cozy and comfortable. This approach has not been carried over into modern architecture, creating an economic and gender divide in modern Somali society and rendering the land unusable for grazing and farming.

In aqals built today, we see the use of mass-produced fabrics, scraps and packages instead of woven mats and plants, often creating a dirty and tattered look rather than a cozy and ornamental one.

Aqal from Hargeisa, Somaliland // Aqal from North Kenya

Asia

Huts in Mesopotamian marshes

Between two rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates, we once witnessed the rise of a prosperous Sumerian civilization. Of course, we are amazed by their huge ziggurats and temples, but only the upper class could visit and live in such places. Ordinary people lived in floating reed houses that could be easily dried, reassembled, and rebuilt after floods.

While their civilization fell and gradually became what we know today as Iran, Iraq and Syria, the tradition of constructing these beautiful ornamental floating reed buildings was inherited by the Ma’Dan, also known as the Marsh Arabs, who migrated to these areas between the 8th and 13th centuries.

Mudhifs, floating reed huts, 1970-80s

In recent years, however, a long line of floating homes and agriculture has been forcefully damaged by the Iraqi government.

«Many of the marshes' inhabitants were displaced when the wetlands were drained during and after the 1991 uprisings in Iraq. The draining of the marshes caused a significant decline in bioproductivity; following the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the overthrow of the Saddam Hussein regime, water flow to the marshes was restored and the ecosystem has begun to recover. » U.S. National Aeornautics and Space Administration, 2008

It is difficult to say whether the community and ecosystem will ever be fully restored, but currently thousands of Ma’dan people are once again living in beautiful reed houses.

Mesopotamian marshes before drought, 1980-s

Another example of an ancient tradition that has survived almost unchanged to this day is the yurt. In the 9th and 10th centuries, the Cumans flourished in Eurasia, a nomadic people who lived in mobile tents, often brightly decorated with Tengrian ornaments.

A similar lifestyle has been handed down to the Mongols, who still very often prefer living in yurts to houses and apartments.

Cuman houses, theatrical illustration by Ivan Bilibin

There are many advantages to living in a yurt. Yurts are cold in summer and warm in winter, it’s easy to visit your various friends and relatives from all over the country and stay for a while, it’s easy to host guests in additional yurts, it’s affordable, it’s easier to herd horses while living in a yurt.

Some people simply prefer the freedom of seeing the plains and the sky above every day, and keeping alive a tradition they’re proud of.

«Yurt» is a word used only by outsiders; Mongolians themselves call yurts «gers», which translates simply as «home.

Ger district in Ulaanbaatar

But it is not a choice for everyone. Many Mongolian citizens simply can’t afford to own a home in the capital, but still have to commute to work every day.

In modern times, however, their nomadic lifestyle is once again facing many difficulties. Most importantly, a rapidly growing economy and population using coal to heat their yurts in the winter is too harmful to the environment. Ulanbataar currently has dangerous levels of air pollution due to both the harvesting and use of coal.

The government has continually tried to solve the environmental problem by introducing central heating, alternative energy sources, and tree planting reforms, but we have yet to see significant results from any of these actions.

Yurt right next to a panel house, yurt part in specialized shops

Bahay Kubo is a Philippine house that would not generally be considered mobile were it not for the tradition of bayanihan, «which refers to a spirit of communal unity or effort to achieve an objective». © Cruz Rachelle «THE BAYANIHAN: Art Installation at Daniel Spectrum». Basically, it means that when needed, people work together to lift and move the entire house to a new location.

Bahay Kubo // An example of «bayanihan»

Bahay Kubo’s light and elevated architecture is meant to protect the house from floods and storms, but its lightness and mobility actually inspired western architects to invent a more stable and durable building instead.

William Le Baron Jenney, an American architect, was originally inspired to create the first skyscraper after seeing the structure and stability of the Bahay Kubo, and we know that this structure and idea has only become more common and essential in modern times.

An elevated Bahay Kubo // Leiter II Building, South State & East Congress Streets, Chicago

Europe

Mitato, Crete // Chozo, Spain // Clochan, Ireland

Temporary shelters made of stone were very common in all European mountain regions — northern British Isles, southern Spanish and Italian regions.

Sometimes their construction and residence was a spiritual and religious practice, such as the Scottish Cleits, but most commonly they were used by shepherds and travelers to take a quick rest or store supplies, such as the Spanish Chozo huts or the Greek Mitato.

Mitatos are still used to store and process all kinds of traditional goat cheeses and are a relatively famous Crete tourist attraction.

Cleit, St Kilda Isles, Scotland

The Chronicles of Jehan Froissart, 15th century // War Tent from Narnia movie set, 2008

Perhaps because of a harsher climate and a tradition of settling down to farm, we don’t usually associate post-medieval Europe with the tents and huts still so common to nomadic communities. However, we can see a clear pattern of where mobile construction still proved its worth and continued: in times of war.

Lavvu, 1900s // Kohte, 1960s

Once the Romans used their tents to build huge war camps and expand their empire, Europe’s plains and forests have always provided a good environment and cover for traveling scouts, partisan movements, and fleeing refugees.

Another special example are the Kohte tents used by German scouts during the Second World War. Kohtes are based on Goahti and Lavvu, tents used by indigenous Sami people, it’s structure allows it to be easily assembled and moved, can fit several people. Smoke hole at the top allows for a fire to be lit if necessary, or can be covered with another fabric in rainy weather.

Goahti, a Sami hut

Lavvu-inspired glamping tents, Norway

Today, laavus inspire people to a much more innocent use — it’s one of the trendy glamping tents, cozy and aesthetically eye-catching.

Ecotourism gained its popularity in the 2010s, wealthy and middle class, tired of city asphalt and tall buildings, crave both the comforts of civilization and the coziness of nature.

Lavvu-inspired glamping tents, Norway

An interesting practice for temporary housing was invented in southern Italy with trulli houses.

Trulli are small, easily demolished and easily reassembled conical dry stone buildings… And the reason for their destruction was tax evasion. When tax inspectors visited the area, people would quickly demolish their extra houses, claiming they had less property and thus paid less taxes.

Trulli houses, Italy

Regular camping and tents, as we usually think of them today, were actually invented relatively recently due to an increased interest in hunting and mountaineering.

Inventors began to customize their designs, display them at exhibitions, and patent them under their last names. For example, the A-shaped, lightweight Whymper tent was designed and named after English mountaineer Edward Whymper, and a larger and wider Mummery tent was named after its designer, alpine climber Fred Mummery.

Whymper tent, 1850s // Mummery tent, 1860s

Edward B. White and Walter Mansur camping in the woods, 1880-90s

America

While the indigenous peoples of the Americas obviously had their own examples of huts and shelters, we find it reasonable to continue to discover examples of temporary buildings and their uses in a chonological order.

Hooverville in Alabama, 1920-s // Hooverville in Seattle, 1933

USA is famous for its tornadoes, economic crises and extreme housing prices, which provides us with another example of portable hoses — emergency need.

During the Great Depression of the 1920-30s, there were hundreds of shantytowns across the country called Hoovervilles, «named after Herbert Hoover, who was President of the United States during the onset of the Depression and was widely blamed for it.» © Hans Kaltenborn, 1956

How many and what kind of people lived in Hooverville is still debated. Some people claim that they were only used by temporarily unemployed laborers, while other historians claim that entire families lived there. Some Hoovervilles had stone and brick houses, if construction workers could spare the time and effort to build them.

As the economy improved, Hoovervilles were torn down and replaced with new housing by American government.

However, the issue of housing kept coming up. Today, there are more than a hundred tent cities across the U.S., housing more than a thousand hundred homeless people.

Tent city in Nevada, USA, 2008

Illustration of First Circus in USA, 1768

And, well, just as there are tents for the poor, there are also huge and ornate tents for the rich.

Tent revivals, or tent meetings, are gatherings of Christian believers that can hold larger audiences than relatively modest Protestant churches, attempting to attract new followers through these open spaces and communal gatherings.

Such tent meetings are often used by televangelists or other Christian-adjacent temporary cult-like movements.

Tent revival marquee tent, Pennsylvania, USA, 2008

Revival Tent Meeting, Appalachia, USA, 1980

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can see that people all over the globe and throughout history have used portable buildings for all sorts of purposes, sometimes by choice, sometimes out of necessity.

It is difficult to say whether handmade huts and tents can really be a solution to the world’s housing crisis… But we can see and follow the pattern of sustainability.

There is clearly no simple solution of panel houses for everyone everywhere. People end up using buildings that are appropriate for their current environment, climate, way of life and culture — and yet some traditions have survived and been passed down, while even the civilization that first invented them has itself collapsed.

The first thing we study in different cultures is architecture — and that includes common huts and houses too.

«The Field of the Cloth of Gold», Hans Holbein the Younger, 1545

Mustafe Abdillahi Omar, Funke Folasade Fakunle, Adebayo Adeboye Fashina «The status quo of Somaliland construction industry: A development trend»

https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-styles/a2516-the-future-of-portable-architecture/

Farah Alkhoury, Aditi Shetye «The Ma’dān Tribes of Iraq: A case for Environmental Refugees» https://centerforspatialresearch.github.io/conflict_urbanism_sp2021/2021/04/18/Alkhoury_Shetye.html

Nik Wheeler «The Marsh Arabs of Iraq» https://www.visapourlimage.com/en/festival/exhibitions/irak-les-arabes-des-marais

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2c/Reed_houses%2C_Iraq_marshes_1978_-_panoramio.jpg